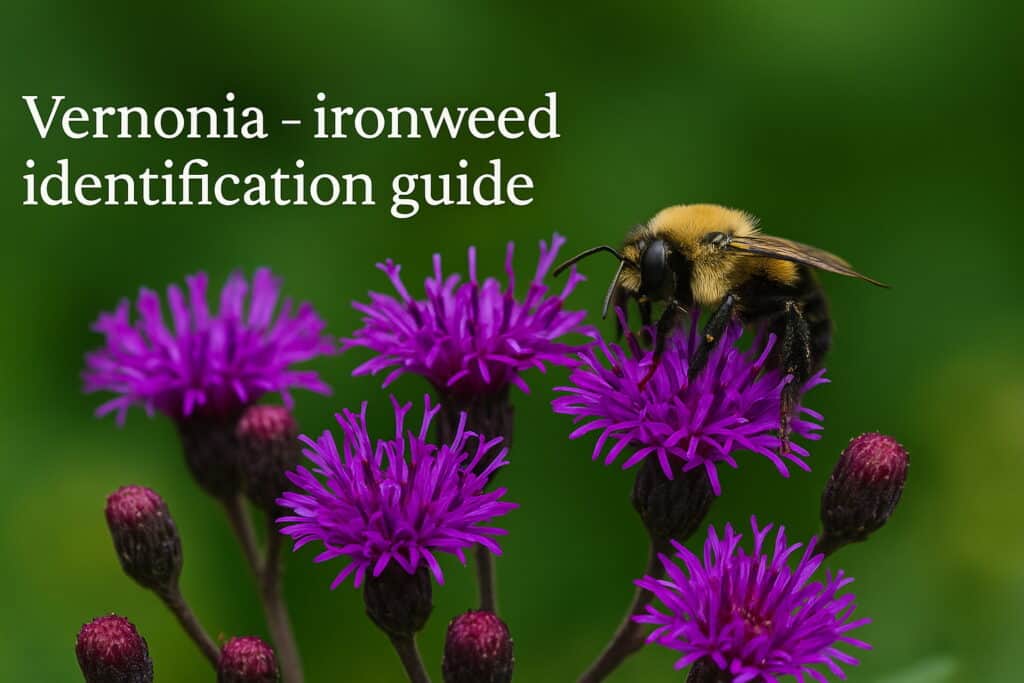

Among the boldest native wildflowers of late summer, Vernonia—commonly known as ironweed—rises like a regal torch above meadows, wet prairies, and woodland edges across the Eastern United States. With their striking, deep purple blooms and unwavering, upright stems, these plants command attention while quietly supporting an entire cast of native bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects.

Celebrate ironweed not only for its ornamental beauty but for its extraordinary ecological value. From the towering Vernonia gigantea, whose height echoes the grandeur of old field succession, to the compact, finely textured Vernonia lettermannii ‘Iron Butterfly’, each member of this genus plays a distinct role in seasonal biodiversity and habitat restoration.

This identification guide has been carefully prepared to help gardeners, land stewards, educators, and native plant advocates recognize and distinguish the diverse species and cultivars of Vernonia most suitable for coastal and Piedmont landscapes, such as those found throughout the Delmarva Peninsula. By examining key features—leaf shape, growth form, flower structure, and bloom timing—you’ll not only gain insight into their proper identification, but also learn how to design with purpose. Whether you’re restoring a meadow, building a pollinator corridor, or simply enriching your home garden, Vernonia offers an inspiring blend of structure, resilience, and wild charm.

“In a world increasingly detached from nature, planting Vernonia is a quiet act of rebellion—one that restores beauty, balance, and biodiversity right at our feet.”

Vernonia Cultivar Identification Guide

Vernonia angustifolia ‘Plum Peachy’

Leaves: Narrow, linear to lance-shaped, soft texture

Stand Form: Upright clumping, less spreading than V. noveboracensis

Height: 3–5 feet

Leaf Size: 3–6 inches long, narrow (1/4 to 1/2 inch wide)

Flower Formation: Loose terminal clusters of small composite flower heads

Flower Color: Rich magenta-purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–October)

As a selection of the southeastern native V. angustifolia, ‘Plum Peachy’ brings high ecological value to dry, sandy, sunlit sites such as the Coastal Plain. Its narrow leaves and late-season blooms support a range of native pollinators, especially small bees and skippers. Its nectar-rich flowers are a magnet for migrating monarchs and other insects when few other native species are in bloom.

Native Range: Southeastern U.S., primarily from Alabama to South Carolina

Vernonia arkansana

Leaves: Lanceolate to oblong, coarser than V. angustifolia

Stand Form: Tall, upright, often bushy with strong stems

Height: 4–6 feet (can reach 7 feet in rich soils)

Leaf Size: 6–10 inches long, broader than V. angustifolia

Flower Formation: Dense dome-shaped heads in branched clusters

Flower Color: Deep purple to red-purple

Flowering Season: Late summer into early fall (August–September)

Native to the Ozarks and Southern Plains, Vernonia arkansana supports robust nectar webs and contributes to late-season biodiversity in tallgrass and prairie ecosystems. Its large, domed flower heads attract a wide range of pollinators, while its foliage may serve as a larval host for moths and butterflies. Its value increases in managed meadows and ecological restoration settings.

Native Range: South-central U.S., especially Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri

Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

Leaves: Similar to species but may be slightly larger

Stand Form: Very tall and upright, robust with thicker stems

Height: 6–8 feet

Leaf Size: 8–12 inches long, broad lanceolate

Flower Formation: Large, bold clusters on top of strong stems

Flower Color: Deep purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–September)

A cultivar bred for bold stature and flowering performance, ‘Mammuth’ retains the ecological benefits of its native parent, attracting bees, butterflies, and native wasps with dense, late-season blooms. Though not a wild genotype, it functions as a reliable pollinator plant in designed habitats.

Native Range of Parent Species: South-central U.S.

Vernonia gigantea

Leaves: Broad lance-shaped, rough and hairy on surface

Stand Form: Towering, upright with occasional branching

Height: 6–10 feet

Leaf Size: 8–15 inches long, noticeably broad

Flower Formation: Loosely branched clusters of small composite blooms

Flower Color: Bright violet to purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–September)

One of the most widespread eastern ironweed species, V. gigantea thrives in moist meadows, streambanks, and woodland margins. It’s a keystone nectar source during late summer and early fall for a broad spectrum of pollinators. Its upright, towering form also creates vertical habitat structure important for wildlife corridors.

Native Range: Eastern and Southeastern U.S., from Pennsylvania to Florida and west to Texas

Vernonia gigantea ‘Purple Pillar’

Leaves: Similar to species, possibly slightly narrower

Stand Form: Tall, narrow, columnar habit

Height: 6–8 feet

Leaf Size: 6–10 inches long

Flower Formation: Tight clusters along the top of vertical stems

Flower Color: Deep purple

Flowering Season: August–September

A horticultural selection of V. gigantea, this cultivar maintains much of the species’ ecological value while offering a narrower form for landscape use. It retains its attractiveness to bees and butterflies, particularly native bumblebees, without compromising its habitat function.

Native Range of Parent Species: Eastern U.S.

Vernonia glauca

Leaves: Broad lanceolate, bluish-green hue with slightly glaucous coating

Stand Form: Upright but looser than other species

Height: 3–5 feet

Leaf Size: 6–8 inches long

Flower Formation: Rounded clusters of purple flowers

Flower Color: Soft to medium purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–September)

V. glauca is a Mid-Atlantic native with a restricted range, found mainly in dry, open woodlands and rocky outcrops. Its glaucous foliage and moderate height make it a valuable species for restoration in upland coastal and Piedmont ecosystems. Though less commonly available in trade, it serves as a regional biodiversity anchor plant.

Native Range: Maryland, Virginia, and parts of Pennsylvania

Vernonia lettermannii ‘Iron Butterfly’

Leaves: Very fine, thread-like, deeply dissected and ferny

Stand Form: Dense, bushy mound, compact and upright

Height: 2–3 feet

Leaf Size: 3–5 inches long but very thin (almost needle-like)

Flower Formation: Dome-shaped heads in dense terminal clusters

Flower Color: Bright purple

Flowering Season: Late summer (August–September)

This compact, thread-leaf cultivar of V. lettermannii is widely praised for its pollinator activity. Originating from Arkansas’s Interior Highlands, it performs especially well in dry, sandy soils. Its ferny foliage provides season-long structure, while its dense flowers attract native bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects.

Native Range of Parent Species: Arkansas and Oklahoma

Vernonia missurica

Leaves: Lanceolate, slightly serrated, rough to touch

Stand Form: Upright, bushy, slightly arching stems

Height: 3–5 feet

Leaf Size: 5–8 inches long

Flower Formation: Broad, flat-topped corymbs of purple flowers

Flower Color: Medium to bright purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–September)

Well-suited to prairie restorations, V. missurica provides abundant nectar and modest structural height, complementing other mid-tier natives. Its roots stabilize soils and its flowers support pollinators into autumn, making it ideal for ecological transition zones.

Native Range: Central U.S. including Missouri, Kansas, and surrounding states

Vernonia ‘Southern Cross’

Leaves: Narrow and finely textured, between threadleaf and lanceolate

Stand Form: Upright and dense, with symmetrical form

Height: 3–4 feet

Leaf Size: 4–6 inches, slender

Flower Formation: Tight clusters on stiff stems

Flower Color: Rich purple

Flowering Season: Late summer (August–September)

This likely hybrid between V. angustifolia and V. lettermannii was developed for aesthetic form and garden use, but its value to pollinators remains high. The hybrid vigor produces a strong, floriferous plant that supports a diversity of insects while maintaining a tidy profile.

Native Range: Cultivated hybrid with Southeastern U.S. parentage

Vernonia noveboracensis

Leaves: Long, narrow lanceolate, tapering to fine points, rough-edged

Stand Form: Upright, often colony-forming by rhizomes

Height: 5–8 feet (occasionally to 10)

Leaf Size: 6–10 inches long

Flower Formation: Large, loose corymbs of multiple small heads

Flower Color: Bright reddish-purple

Flowering Season: Late summer to early fall (August–September)

A true Mid-Atlantic and Coastal Plain keystone species, V. noveboracensis plays a vital role in pollinator networks, wetland buffers, and stormwater filtration landscapes. With its rhizomatous growth, it forms large colonies that bloom in vivid purple, supporting monarchs, fritillaries, and dozens of native bee species.

Native Range: Eastern U.S., from Massachusetts to Georgia and inland to Ohio

Vernonia baldwinii

Leaves: Oblong to lanceolate, slightly hairy

Stand Form: Upright, airy, and branched

Height: 3–5 feet

Leaf Size: 4–7 inches long

Flower Formation: Loose clusters with widely spaced stems

Flower Color: Magenta to lavender-purple

Flowering Season: August–September

This adaptable ironweed is native to drier southern and central plains, where it thrives in full sun and shallow soils. It supports solitary bees and butterflies, including monarchs, and is gaining recognition as a durable addition to native gardens and roadside restoration projects.

Native Range: Central and Southern U.S., including Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri

The Story of Ironweed: A Deeper Look at Vernonia

Like many of the most meaningful plants in our native landscapes, Vernonia wears its significance modestly. Its stems don’t clamor for attention until late summer, when the rest of the garden begins to slow. Then, with timing as precise as a symphony’s final crescendo, ironweed erupts in a blaze of purple—demanding our notice and drawing in every bee, butterfly, and wandering eye that happens upon it. But behind the vibrant blooms lies a story that stretches across continents, cultures, and centuries.

The genus Vernonia belongs to the aster family (Asteraceae), one of the largest and most ecologically important plant families in the world. Globally, the genus includes over 1,000 described species, with the greatest diversity found in Africa, Southeast Asia, and tropical regions of the Americas. The name Vernonia honors the 17th-century English botanist William Vernon, who collected and catalogued plants in Maryland during the colonial period—just a stone’s throw from the very landscapes where our native Vernonia noveboracensis still thrives.

In the Eastern United States, roughly a dozen species are native, from the towering V. gigantea of moist meadows to the wiry, thread-leafed V. lettermannii of the dry Ozark glades. Each species has adapted to a particular ecological niche, showing resilience in both wet and dry conditions, colonizing abandoned fields, stabilizing roadsides, and thriving in stormwater-prone areas. Their late-summer flowering makes them a lifeline for monarch butterflies during migration, as well as countless native bees, skippers, syrphid flies, and beneficial wasps. In some communities, Vernonia is more than an ecological performer—it’s a keystone.

But its significance doesn’t end in the pollinator garden. For centuries, indigenous peoples of North America made use of ironweed for medicinal purposes. The Cherokee, among others, used the roots to treat post-partum recovery, indigestion, and fevers. The plant’s tough stems and bitter taste gave rise to its common name—“ironweed”—a reference not just to its durability in wind and rain, but also to its bitter compounds, which include lactones and flavonoids with potential herbal benefit. Though rarely used in contemporary herbalism, ironweed still holds a place in the ethnobotanical archives of early American healing traditions.

In more recent years, Vernonia has crossed into international horticulture, especially in Europe, where garden designers like Piet Oudolf have championed its structural form and seasonal drama. One of his preferred species, V. crinita (according to the Flora of North America, USDA Plants Database, and Kew’s Plants of the World Online, the name Vernonia crinita is no longer taxonomically accepted and has been revised as a synonym of Vernonia arkansana.)now features prominently in naturalistic meadows and planting schemes from the Netherlands to New York. In these contexts, ironweed is no longer just a “wildflower”—it becomes sculpture in motion, a native plant elevated through design.

Here on the Delmarva Peninsula, we are fortunate to host several Vernonia species naturally. They belong to the soil, to the shoreline, to the succession of growth and decay that defines our native ecology. By growing and understanding ironweed, we participate in something older than ourselves—a shared ecological language between plants, pollinators, and people. And in that story, Vernonia stands tall—resilient, purple, and proud.

In-conclusion

As stewards of the land—whether at home, in community gardens, or in public spaces—we have a responsibility to plant with intention. Vernonia, with its commanding form and magnetic draw for pollinators, offers us more than a late-season floral display; it gives us an opportunity to restore balance, offer nourishment, and bring beauty into wild and cultivated spaces alike. By learning to identify these species and understanding their ecological roles, we begin to see gardening not just as decoration, but as restoration in motion.

At the Delaware Botanic Gardens, we’ve learned firsthand that the most meaningful landscapes aren’t always the tidiest—they’re the ones that hum with life, shift with the seasons, and reconnect people to the pulse of the natural world. In the end, identifying ironweed is more than a botanical exercise—it’s a step toward remembering what belongs here and why.

Further Reading & References – Vernonia (Ironweed)

General Ironweed Resources

- USDA Plants Database – Vernonia genus

- Xerces Society – Pollinator Conservation Resources

- Pollinator Partnership – Ecoregional Planting Guides

- Mt. Cuba Center – Native Plant Trials: Vernonia

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Native Plant Information Network

Species-Specific References

Vernonia angustifolia

Vernonia arkansana & ‘Mammuth’

Vernonia gigantea & ‘Purple Pillar’

Vernonia glauca

Vernonia lettermannii ‘Iron Butterfly’

Vernonia missurica

Vernonia noveboracensis

Vernonia baldwinii

Vernonia ‘Southern Cross’

- Mt. Cuba Center Evaluation – Hybrid Forms

- Ecological Landscape Alliance – Cultivars in Native Gardens