How to Collect, Clean, and Store Native Plant Seeds for future generations and local seed diverstiy.

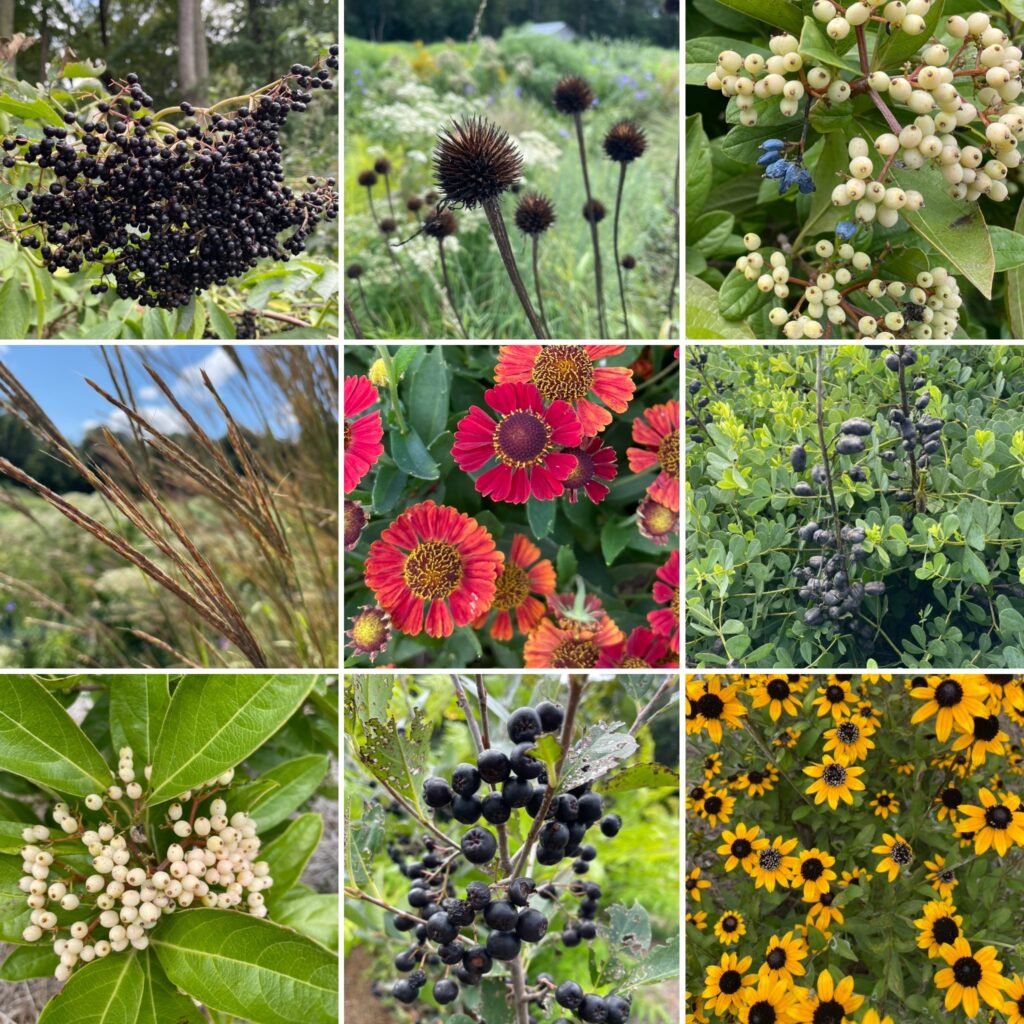

I have loved collecting seeds with memories of hedgerows full of native blooms and berries. Seeds are a great gift and a meaningful reminder of new life and regeneration. Enjoy my guide to collecting, storing, and conserving native plant seeds for wildlife and garden sustainability, and a. colorful pollinator filled future.

Collecting, cleaning, and storing your own native plant seeds can offer many benefits, especially for gardeners, ecologists, and conservationists who want to support local ecosystems and promote sustainability.

Here are some great reasons to start collecting your own native plant seeds, and sharing them with some friends.

Preserves Local Biodiversity

Collecting native seeds helps preserve local plant genetics, which are often best suited to thrive in the unique soil, climate, and conditions of a particular region. By growing plants that are well-adapted to their environment, we help maintain the delicate balance of local ecosystems, providing food and habitat for native wildlife.

Supports Pollinators and Wildlife

Native plants are essential for supporting pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and birds, as well as other wildlife. Many native plants have evolved in tandem with local species, providing them with specific resources and shelter. By collecting and planting these seeds, we can create or restore habitats that benefit a wide array of native species, helping boost biodiversity.

Cost-Effective and Sustainable

Harvesting seeds from existing native plants reduces the need to buy seeds or plants each year, offering a sustainable and economical way to expand gardens and natural areas. Additionally, by using seeds collected locally, gardeners can help decrease the demand for commercial production, reducing the carbon footprint associated with large-scale nursery operations.

Promotes Resilient Plants

Seeds collected from plants that have successfully thrived in local conditions are likely to produce resilient offspring. This natural selection process favors plants that are tough and adaptable to local pests, diseases, and environmental stressors, resulting in a more resilient landscape over time.

Encourages Self-Sufficiency and Engagement with Nature

Gathering and managing native seeds fosters a deeper connection to the natural world. Gardeners and stewards develop a greater appreciation for the life cycles of native plants and the ecosystems they support. Seed collection also encourages self-sufficiency, giving individuals control over what grows in their gardens and contributing to a sense of accomplishment and stewardship.

Aids in Habitat Restoration and Conservation Projects

For conservationists, seed collection is a valuable tool for restoring degraded landscapes. Native seeds can be used in rewilding efforts and habitat restoration projects, helping to establish sustainable plant communities that will stabilize soil, reduce erosion, and improve water quality. Storing seeds ensures a ready supply for future projects, especially if rare or threatened species are involved.

Promotes Seed Diversity and Genetic Variation

When you collect seeds from a range of plants within a species, you increase the genetic diversity of your seed stock, helping to safeguard plant populations against disease, climate variability, and pests. This diversity is essential for the long-term survival and adaptability of plant communities.

Tips for Collecting, Cleaning, and Storing Native Seeds:

Collection: Always collect seeds ethically, leaving enough for natural regeneration and wildlife. Choose seeds from healthy, mature plants.

Cleaning: Remove any debris, husks, or seed coatings that could harbor mold or pests.

Storage: Store seeds in a cool, dry place, in breathable bags or envelopes. Label each with the species name and collection date for reference.

Collecting and saving native seeds is a simple yet impactful practice that contributes to a sustainable future, promotes biodiversity, and reconnects people with their local environment.

Types of Native Plant Seeds and Storage Requirements

Dry Seeds (e.g., Milkweed, Coneflower, Black-eyed Susan)

Characteristics: These seeds naturally dry out on the plant before dispersal, often from plants that grow in open, sunny habitats.

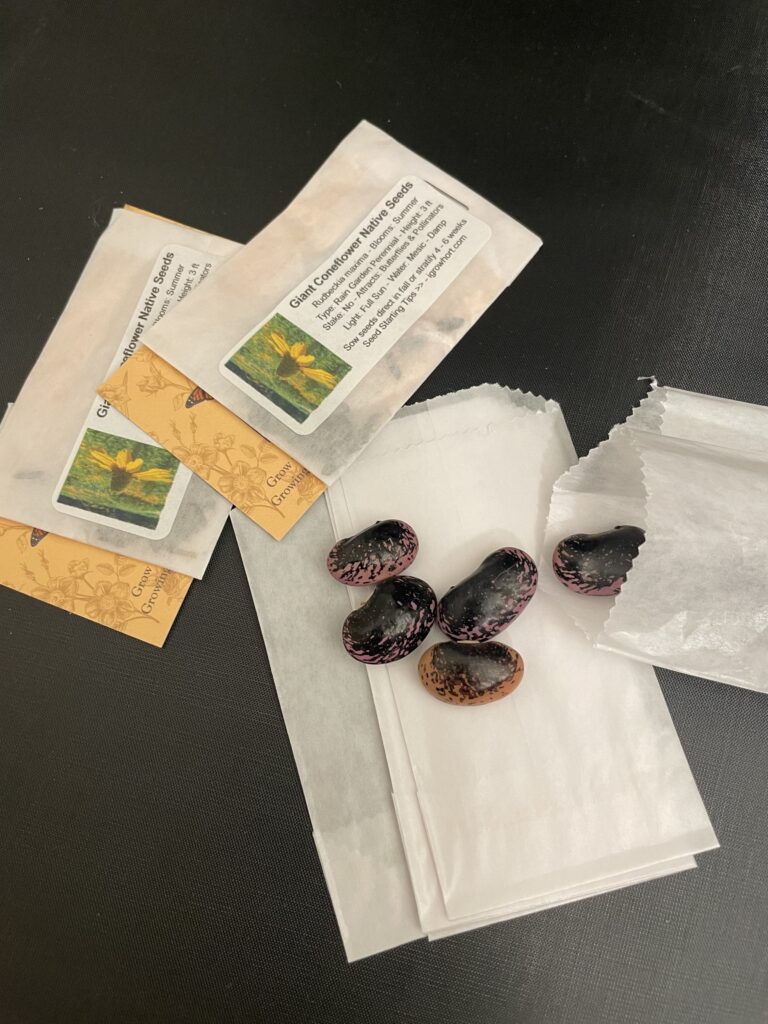

Collection: Harvest dry seeds directly from seed heads, pods, or capsules when they have turned brown or begun to split open. Common dry seeds include milkweed (Asclepias spp.), purple coneflower (Echinacea spp.), and black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta).

Cleaning: Gently remove any chaff (seed coverings or plant debris). Avoid crushing the seeds while handling.

Storage: Store seed for cleaning in a brown grocery bag, for fine seed place paper towel in the bottom to catch small seeds. Once dry gentle shake the bag to allow seeds to fall, transfer seed heads to a second bag for further cleaning.

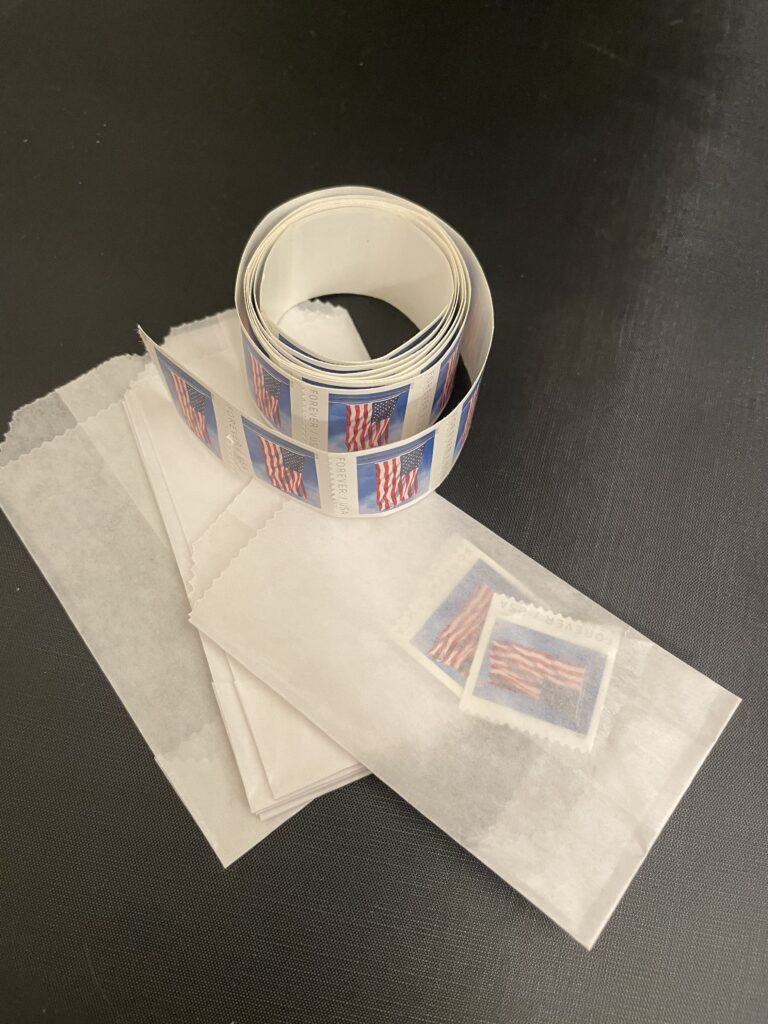

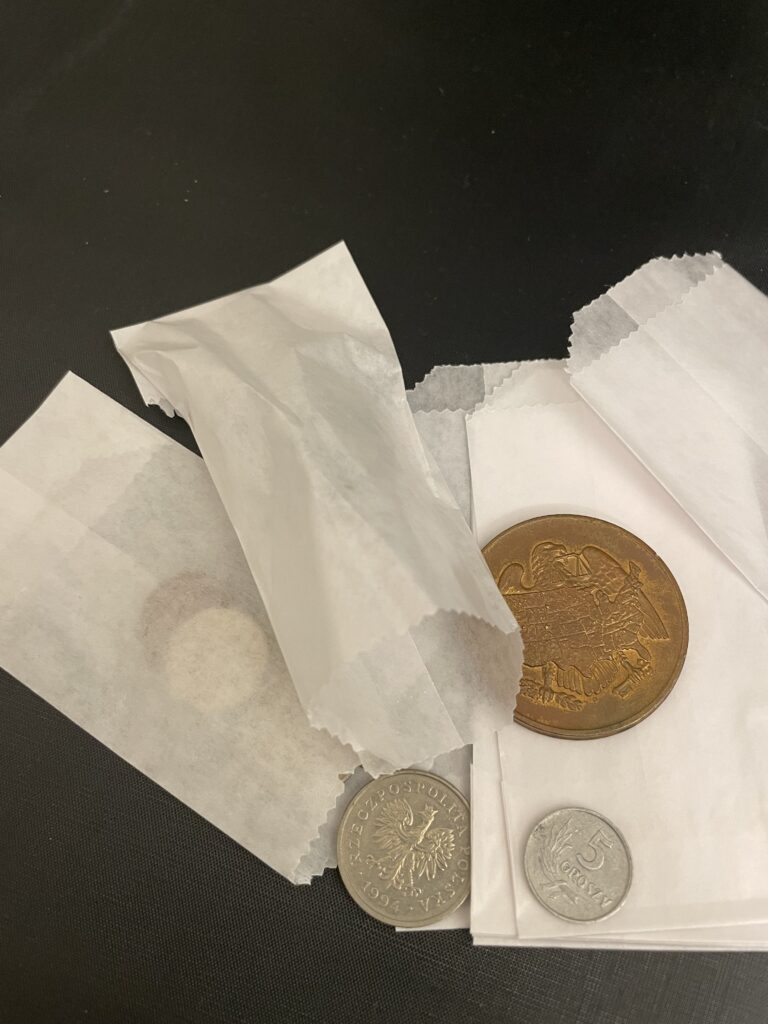

Clean seeds can be stored in glassine envelopes, often used by collectors of coins and stamps. These are the perfect size for many seeds and allow you to share them with friends. Store in a cool, dark, and dry place, ideally with temperatures around 32-41°F (0-5°C). You can use the bottom drawer in your refrigerator to maintain these conditions. Click photo to purchase.

Special Notes: Cold stratification (placing seeds in moist sand or vermiculite in the refrigerator for 30-60 days) is often required to break dormancy for spring planting, especially for milkweed.

Fleshy Fruit Seeds (e.g., Viburnum, Elderberry, Serviceberry)

Characteristics: Seeds from fleshy fruits are often dispersed by animals and need to be extracted from the fruit pulp for optimal storage.

Collection: Collect ripe berries or fleshy fruits when they’re fully mature, usually in late summer or fall.

Cleaning: Remove seeds from the pulp by soaking them in water and gently scrubbing them free. The pulp can inhibit germination, so ensure seeds are thoroughly cleaned.

Storage: After drying, store these seeds in a cool, dry place. Some seeds, like those of serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.) or elderberry (Sambucus spp.), benefit from cold stratification over winter for a few months to simulate seasonal conditions.

Special Notes: These seeds may require a warm stratification period (3-6 months in room temperature conditions) followed by cold stratification to trigger germination.

Winged or Wind-dispersed Seeds (e.g., Maple, Ash, Sycamore)

Characteristics: Winged seeds, such as those from maple trees (Acer spp.) and sycamore (Platanus spp.), typically rely on the wind to scatter and are well adapted to fall in open areas.

Collection: Collect these seeds as they fall, typically in late summer or early fall. Maple seeds (samaras) are easily collected when they are dry and brown.

Cleaning: Separate the wings if possible, though this is optional as long as the seed itself is intact.

Storage: Store in a dry, cool environment. Many wind-dispersed seeds require cold stratification (1-3 months) before planting.

Special Notes: For certain maple species, it’s best to plant fresh, as their seeds have a short viability period.

Capsules and Pods (e.g., Lupine, Penstemon, Wild Indigo)

Characteristics: Seeds from plants that form pods or capsules (e.g., lupine, Penstemon, wild indigo) are typically dry and relatively easy to collect.

Collection: Gather seeds from capsules or pods when they are brown and beginning to split open. Timing is essential, as these seeds can quickly fall.

Cleaning: Remove any remaining plant material, being careful to avoid damaging the seeds.

Storage: Store in a cool, dry place, ideally in a paper envelope within a larger sealed container. Seeds like wild indigo (Baptisia spp.) may need scarification (scratching or nicking the seed coat) before planting to allow water to penetrate and trigger germination.

Tiny or Dust-like Seeds (e.g., Lobelia, Cardinal Flower)

Characteristics: Some native plants, like lobelia (Lobelia cardinalis) and foxglove, produce very tiny seeds that resemble dust.

Collection: Collect from seed heads when they are fully dry. Shake seed heads over a paper plate or tray to catch the fine seeds.

Cleaning: Separate seeds from the chaff as much as possible. These seeds are delicate, so handle carefully to avoid loss.

Storage: Store in a small, sealed container. Place silica gel packets in the container to help maintain low moisture. Due to their small size, they are sensitive to temperature changes, so refrigeration can help prolong viability.

General Seed Storage Tips

Labeling: Always label your seed containers with the plant species, collection date, and any special notes (like stratification needs). This will help you keep track of viability and ensure proper planting times.

Moisture Control: Most seeds last longer if stored dry. Use silica gel packets in your storage containers to keep moisture low.

Temperature: A consistent, cool temperature between 32-41°F (0-5°C) is ideal for most seeds. Refrigerators work well for smaller quantities.

Viability Check: Test viability by performing a simple water test (floating seeds in water; viable seeds often sink) or planting a few to check for germination.

Benefits of Following Seed Storage Best Practices

By carefully following storage practices for each type of seed, you ensure they remain viable for longer periods, extending your ability to plant them at the optimal time and preserving the genetic material of valuable native plants. Proper storage allows you to contribute to habitat restoration and create diverse, resilient gardens year after year.

In summary, understanding the storage needs of different seed types enhances the effectiveness of native plant restoration, creating beautiful and ecologically rich landscapes. With good seed-saving practices, gardeners and conservationists alike can play a pivotal role in sustaining native biodiversity.

Seed viability is essential to consider when collecting and storing seeds, as it impacts how long seeds remain capable of germinating under suitable conditions. Viability can vary widely among species—some seeds, like many native wildflowers and prairie plants, can remain viable for several years if stored correctly, while others have a shorter life span and need to be sown within a season. Factors like seed type, storage conditions (temperature, light, and humidity), and natural dormancy mechanisms also play a role in how well seeds remain viable.

In addition to maximizing viability, ethical and sustainable seed collection is crucial. Here’s why it’s important not to collect all the seeds and to leave some for the ecosystem:

Support for Wildlife: Seeds are a crucial food source for birds, mammals, and insects, especially as seasons change. For instance, finches, sparrows, and other seed-eating birds rely on seeds from native plants in the fall and winter. Leaving a portion of seeds ensures that wildlife has a consistent and reliable food source, helping to support biodiversity in your area.

Natural Regeneration: In natural ecosystems, seeds that fall to the ground provide the next generation of plants, allowing native populations to maintain or expand. When you leave seeds in the landscape, you contribute to this regenerative cycle, allowing nature to replenish the plant population without intervention. This process helps maintain genetic diversity and adapts plants to local conditions over generations.

Balance in Ecosystems: Many native plants have evolved with local fauna, creating a balanced ecosystem where plants, animals, and insects benefit from each other. Overharvesting seeds can disrupt this balance by reducing the resources available for animals and hindering the natural spread of plant species. Collecting a limited amount (often recommended at 10-20% of the available seeds) allows you to take what you need without impacting the health of the ecosystem.

Conservation of Rare or Sensitive Species: Some native plants are rare or have limited populations, so over-collecting seeds can put stress on these already vulnerable species. Leaving seeds for natural dispersal helps to preserve these species in their natural habitats. Responsible collecting practices support conservation and prevent further depletion of species that may already face challenges like habitat loss or climate change.

Ecosystem Resilience: By allowing seeds to remain in their natural habitat, you contribute to the ecosystem’s overall resilience. The seeds that survive in the wild are often the hardiest and best adapted to the local environment. This natural selection process supports stronger, more resilient plant communities that can withstand pests, diseases, and changing climate conditions better than cultivated populations.

Practical Approach for Responsible Seed Collection

When collecting native seeds, a sustainable approach is to:

Harvest seeds selectively, taking only what you need.

Avoid collecting from every plant in a given area.

Collect from multiple plants to ensure genetic diversity.

Leave enough seeds to support wildlife, natural regeneration, and the needs of future generations.

By practicing mindful seed collection, you not only help your garden or restoration projects but also support the entire ecosystem around you. This approach ensures that native plants, wildlife, and local biodiversity thrive together, creating a balanced and sustainable environment.

list of resources, further reading, and references on collecting, cleaning, storing, and germinating native plant seeds:

Bonus Article

When collecting native plant seeds, it’s important to follow legal guidelines, as unauthorized collection can harm ecosystems and is often illegal. Here are key rules and considerations:

State and National Parks:

Collecting seeds or any plant material in U.S. state and national parks is generally prohibited to protect natural habitats. These areas are preserved for ecological integrity, public enjoyment, and conservation purposes.

Violating this rule can lead to fines or other penalties. Always check with park authorities if special permits are available for research or restoration projects.

Public Lands and Preserves:

On federal lands managed by agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or the U.S. Forest Service, seed collection is often restricted. In some cases, special permits may be available, but these are typically for scientific research, conservation, or educational purposes.

Many wildlife preserves, nature conservancies, and ecological reserves have strict prohibitions on seed collection to protect local flora and fauna.

Private Property:

Collecting seeds on private land requires explicit permission from the property owner. Unauthorized collection can be considered trespassing, and harvesting without permission may be illegal.

Some landowners may grant permission if seed collection aligns with conservation or restoration goals. It’s always best to ask and explain your intentions.

Endangered or Threatened Species:

Collection of seeds from plants that are listed as endangered, threatened, or protected under local, state, or federal laws is strictly prohibited. These species are safeguarded to prevent extinction and habitat loss.

Violations of these protections can result in severe penalties, as these laws are designed to protect biodiversity.

Ethical and Sustainable Collection Practices:

Even when seed collection is allowed, follow sustainable practices by collecting a small percentage of available seeds to support wildlife and natural regeneration.

Avoid harvesting seeds from every plant in an area to protect the ecosystem’s health and ensure ongoing plant diversity.

Before collecting seeds, it’s wise to check local regulations or consult with relevant authorities or conservation organizations.

Resources, References, and Recommended Reading for Native Seed Collection and Conservation

1. Seed Collection and Storage Guides

U.S. Forest Service – Seed Collection Guide for Native Plants

This guide offers detailed instructions on collecting and storing native seeds, including specific guidelines for various plant types.

Link: USFS Seed Collection Guide

Native Plant Trust – Seed Collection and Storage Basics

The Native Plant Trust provides guidance on ethical seed collection, cleaning techniques, and seed storage strategies.

Link: Native Plant Trust

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – Seed Information Database

Kew Gardens’ Seed Information Database (SID) offers scientific data on seed biology, storage behavior, and germination for thousands of plant species.

Link: Kew Gardens Seed Information Database

2. Ethical and Sustainable Seed Collection Practices

Xerces Society – Seed Collection Guidelines for Native Pollinator Plants

The Xerces Society provides specific advice for collecting seeds from pollinator plants, emphasizing ethical practices to maintain ecosystem health.

Link: Xerces Society Seed Collection

Native Seed Network – Ethical Guidelines for Native Seed Collection

This resource includes information on sustainable seed collection practices that support native ecosystems.

Link: Native Seed Network

3. Stratification, Scarification, and Seed Germination Techniques

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Seed Stratification and Germination Techniques

This guide from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center covers how to prepare different types of seeds for germination, including cold stratification and scarification.

Link: Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

Prairie Moon Nursery – Seed Stratification and Planting Instructions

Prairie Moon Nursery offers seed stratification instructions for a variety of native plants, with recommendations on preparing seeds for successful germination.

Link: Prairie Moon Nursery

Missouri Botanical Garden – Plant Finder and Germination Tips

Missouri Botanical Garden’s Plant Finder provides germination and storage advice for native and non-native plants, searchable by species.

Link: Missouri Botanical Garden

4. Seed Storage and Longevity

Seed Savers Exchange – Seed Storage Best Practices

Seed Savers Exchange offers general guidelines on storing seeds to maximize longevity, including recommendations for temperature, humidity, and packaging.

Link: Seed Savers Exchange

Millennium Seed Bank (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew) – Seed Conservation Techniques

The Millennium Seed Bank shares professional conservation techniques that support long-term seed storage, suitable for both home gardeners and large-scale conservationists.

Link: Millennium Seed Bank

5. Further Reading on Native Plant Gardening and Seed Saving

“The Seed Garden: The Art and Practice of Seed Saving” by Lee Buttala and Shanyn Siegel

This comprehensive book from Seed Savers Exchange covers techniques for saving seeds from many types of plants, including a section on wildflowers and native species.

Available at: Seed Savers Exchange Bookstore

“Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants” by Douglas W. Tallamy

This book explores the importance of native plants in supporting local ecosystems and provides a foundation for understanding the benefits of using native plants in landscaping.

Available at: Amazon

“The New American Landscape: Leading Voices on the Future of Sustainable Gardening” edited by Thomas Christopher

This book brings together perspectives on sustainable gardening practices, including native seed collection, habitat restoration, and ecosystem health.

Available at: Timber Press